Ok, that’s promising more than I can give, but reading today Paul Guébhard’s account of the Futa Jallon highlands in what is now Guinea in 1910, I discovered his little table that tries quantify the livestock holdings of the Fulɓe pastoralists who lived in the region.

I have been thinking a lot about cattle recently, following the awarding of the Nobel Prize to a trio of scholars who are generally known as “AJR”: Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson and James Robinson. In their famous 2001 paper, they tried to estimate the impact of secure property rights on national incomes, on the assumption that the rules that govern property rights are in much of the world inherited from colonial institutions. I don’t want to go into the criticisms of AJR—many others have—but it is interesting to note that in the ‘new institutionalist’ scholarship that was written in their wake, and in particular that fraction of it devoted to Africa, very little has actually been said about property rights per se, and even less about the kinds of property rights that are important for overwhelmingly agrarian economies. (Pseudoerasmus has made this point on BlueSky at much greater depth).

In this respect, it seems interesting to consider the institutions of cattle ownership in tropical Africa (particularly in those areas outside the main tsetse fly zones), since livestock ownership is the major form of wealth in the arid tropics, where land has little intrinsic market value. I am going to try to write a little bit more about the institutions themselves, but for now, I thought it would be interesting to look at one of the consequences of such institutions. How unequal was ownership?

In total, Guébhard estimates a population of around 400,000 cattle in Futa Jallon, divided up between around 44,000 households (representing, he claims, a population of around 280,000 people).

It is a very summary table, and also of dubious precision: for example, the very largest herds of 50 cattle all seem to be owned by precisely ‘780 households’, as do the herds with 49 cattle, and so on until we reach much lower herd sizes. The accuracy of the right hand side of the Lorenz curve is therefore suspect.

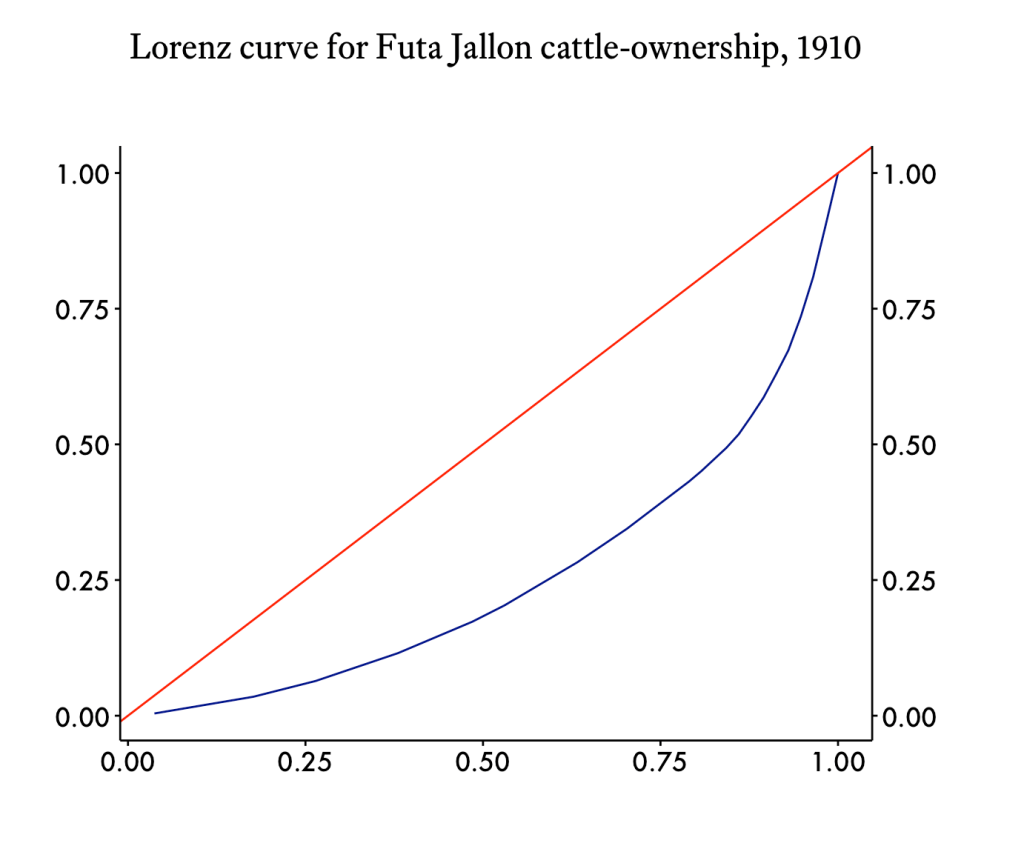

Of course, we would want to have much more information than this to build a proper social table for wealth inequality: cattle-owners, as Guébhard notes, were only around 3 in every 11 people in Futa, for example, and we don’t have any information on any non-livestock wealth. But it is still an interesting exercise to plot the Lorenz curve and calculate the Gini.

The Lorenz curve looks like this:

from which we can calculate the cattle-wealth Gini of 0.28.

Without any directly comparable estimates, it is hazardous to make any broad statements about inequality in early colonial Futa. But it’s interesting that this estimate is in the same ballpark as the Gini (note: for income not wealth) of Botswana in the 1920s (the chart from Hillbom, Bolt, De Haas and Tadei’s paper earlier this year in the EHR)—Botswana being one of the most important cattle-owning societies in Africa in this time.

Overall, though, the number seems relatively low, and this may be for several reasons. The first is that mortality was relatively high in Futa, due to enzootic diseases, like trypanosomiasis. Another, though, may be that cattle redistribution is a relatively important feature of Fulɓe societies—and indeed of many pastoral societies elsewhere.

Leave a comment